The epidemiology of schistosomiasis is shaped by an intricate interaction among human behavior, ecological systems, and the biology of freshwater snails that act as intermediate hosts. Although the disease is fundamentally parasitic, its transmission dynamics are primarily environmental.

Understanding the environmental determinants that influence Schistosoma distribution is therefore central to designing sustainable control programs, planning public health interventions, and developing integrated strategies that align with local ecological contexts.

This paper examines the major environmental parameters that support or inhibit transmission of Schistosoma species and describes how these variables interact with socioeconomic and behavioral factors to create distinct risk landscapes.

One discussion point will also reference pharmaceutical supply chains, using the example of a mebendazole wholesaler as part of broader drug-access considerations within endemic regions.

Hydrology and Water Resource Development

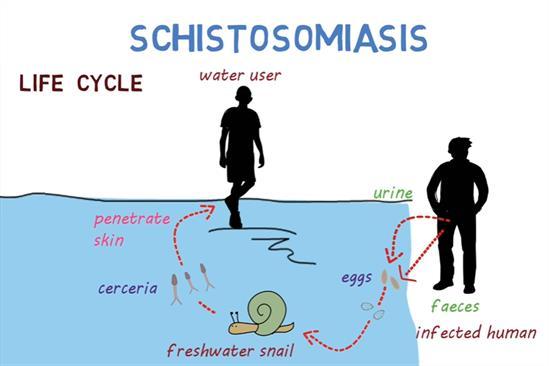

The life cycle of Schistosoma parasites is fundamentally dependent on freshwater bodies that sustain host snail populations. Hydrology the movement, distribution, and quality of water plays a direct role in governing where infections occur. Snail species that serve as intermediate hosts, such as Biomphalaria, Bulinus, and Oncomelania, require particular water conditions to survive and reproduce. Slow-moving or stagnant water is especially conducive to snail population growth, which explains the high transmission rates in lakes, ponds, irrigation canals, and marshlands.

Large-scale water resource development projects, including dams, irrigation systems, and flood-control interventions, frequently alter hydrological patterns in ways that unintentionally intensify schistosomiasis transmission. For example, newly created irrigation canals often increase the shoreline surface area and provide ideal breeding sites for snails.

The stable water levels created by dams reduce seasonal variability that might otherwise suppress snail populations. Moreover, water resource development encourages human settlement and agricultural activity near waterways, increasing contact between people and parasite-infested water. Thus, hydrological modifications can convert previously low-risk regions into significant transmission hotspots.

Climate and Seasonal Variation

Climatic variables particularly temperature, rainfall, and humidity influence both snail ecology and parasite development rates. Temperature affects the growth, reproduction, and survival of host snails, as well as the development speed of the parasite within both snail and human hosts.

Most Schistosoma species flourish in tropical and subtropical climates where water temperatures remain between 20°C and 30°C. Rising global temperatures have extended the potential geographic range of compatible snails, increasing concern about the northward or altitudinal expansion of schistosomiasis into new regions.

Rainfall patterns affect water flow and create or remove breeding sites. Heavy rains may temporarily wash away snail populations, reducing transmission in some areas, but they can also create new pools of standing water that support later population rebounds.

In contrast, drought conditions concentrate human water contact in fewer available water bodies, which can increase localized transmission. Seasonality also drives human behavior, particularly agricultural cycles. In many endemic regions, peak transmission coincides with planting or harvesting seasons when farmers spend prolonged periods in canals or floodplains.

Land Use, Agriculture, and Ecological Disturbance

Agricultural transformation is a major contributor to environmental changes that influence schistosomiasis. Irrigation-based agriculture supports extensive snail habitats, while fertilizers and organic waste promote algal growth that snails feed on, thereby increasing snail proliferation. Additionally, deforestation and the conversion of wetlands for agriculture disrupt ecosystem balances and often create new habitats suitable for snail colonization.

Livestock management can have mixed effects. On one hand, cattle and other animals may increase nutrient runoff into water systems, strengthening ecological conditions for snail growth. On the other, in some settings, grazing reduces aquatic vegetation that snails rely on. The net impact depends on local ecological configurations. Integrated vector management must therefore account for the entire agricultural ecosystem rather than isolated activities.

Urbanization also influences schistosomiasis transmission patterns in two contrasting ways. Improved sanitation infrastructure in urban centers reduces environmental contamination, thereby decreasing the introduction of Schistosoma eggs into water systems. However, unplanned peri-urban expansion often results in inadequate drainage, polluted canals, and informal water collection sites, all of which may create microhabitats conducive to snail survival.

Biodiversity and Ecological Interactions

Natural predators of snails such as fish, crustaceans, and certain aquatic insects play a meaningful role in controlling snail populations. Environments with greater biodiversity generally exhibit lower schistosomiasis transmission because ecological competition and predation accumulate to limit snail density.

Conversely, ecological degradation that eliminates predator species tends to increase snail abundance. For example, overfishing in lakes or rivers can remove predator fish populations and inadvertently facilitate the expansion of snail hosts.

Restoration of ecological balance through reintroduction of predator species or habitat rehabilitation has been explored in several regions as an environmentally aligned means of reducing Schistosoma transmission. These methods complement traditional chemotherapy-based approaches and offer sustainable long-term benefits.

Water Quality and Pollution

Water pollution from industrial waste, agricultural runoff, or untreated sewage affects schistosomiasis in complex ways. Moderate organic pollution often promotes snail growth by increasing food sources such as algae and detritus. Conversely, severe pollution conditions can be toxic to snails and thereby diminish transmission potential. The relationship is non-linear: low-level contamination may raise infection risk, whereas high toxicity may suppress it entirely.

Beyond ecological effects, poor water quality increases human contact with contaminated natural water sources when safe alternatives are unavailable. Communities without reliable drinking water or sanitation infrastructure are more likely to use rivers, lakes, and canals for bathing, washing, collecting water, or recreational activities, all of which heighten exposure to infective Schistosoma cercariae.

Human Behavior, Socioeconomic Conditions, and Access to Health Resources

Environmental factors shape opportunities for transmission, but human behavior determines actual exposure. Daily activities such as fishing, farming, laundry, swimming, and water retrieval link individuals directly to infested water bodies. Public health strategies must therefore integrate behavioral and educational components alongside environmental interventions.

Socioeconomic status also plays a decisive role. Low-income communities are disproportionately exposed to schistosomiasis because they frequently lack access to clean water and sanitation services. Economic activities in rural regions often require direct contact with surface water, reinforcing environmental dependency. Limited access to diagnostics and treatment further entrenches transmission.

Pharmaceutical availability influences disease management outcomes. Although praziquantel is the principal drug used to treat schistosomiasis, broader antiparasitic supply chains also play a role in supporting national programs, particularly in co-endemic areas where multiple helminth infections occur.

For example, a mebendazole wholesaler may support mass drug administration campaigns targeting soil-transmitted helminths, which often coexist in the same ecological and socioeconomic environments as Schistosoma infections. Strengthening these supply networks helps ensure continuity of integrated control programs.

Conclusion

Environmental factors remain central drivers of schistosomiasis transmission. Hydrological changes create new habitats for snail hosts, while climatic variation influences parasite and snail development rates. Agricultural transformation, ecological disturbance, biodiversity loss, and water quality degradation all interact to shape complex landscapes of risk.

As environmental and climatic patterns evolve, schistosomiasis control strategies must increasingly adopt an integrated approach that combines environmental management, improved water and sanitation systems, health education, ecological restoration, and reliable pharmaceutical supply chains.

Only by recognizing the multifaceted environmental dependencies of Schistosoma transmission can public health systems design interventions that achieve durable, long-term reductions in infection and advance toward global elimination goals.